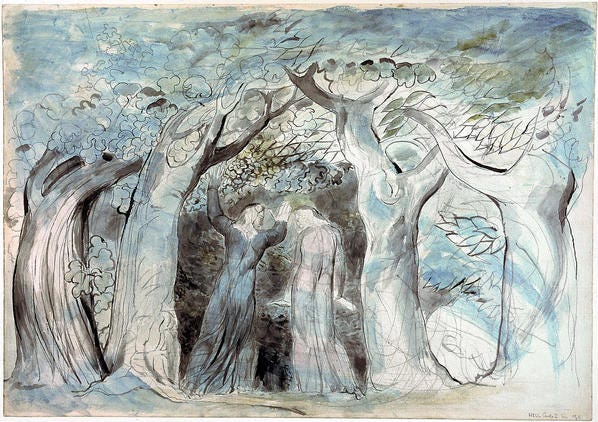

Dante begins his classic poem ‘The Divine Comedy’ with the following lines:

In the middle of the journey of our life I came to myself within a dark wood where the straight way was lost. Ah, how hard a thing it is to tell what a wild, and rough, and stubborn wood this was, which in my thought renews the fear!

(William Blake, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Lost, Dante begins an epic journey that takes him down to the depths of hell and then up to the heights of heaven, before finally meeting his heart’s desire:

But already my desire and my will were being turned like a wheel, all at one speed, by the Love which moves the sun and the other stars.

On my own life journey, I have discovered a deep longing, common to us all I believe, a longing to craft a life for myself that is truly my own, a life that honours and engages my individual uniqueness, my own passions, gifts, dreams and experiences. In psychology, this longing might be described as the desire for self-actualisation or self-realisation. In religion, words like “vocation” or “calling” are often used. And the poet Mary Oliver points to it beautifully in her poem ‘When Death Comes’:

When it's over, I don't want to wonder

if I have made of my life something particular, and real.

I don't want to find myself sighing and frightened,

or full of argument.

I don't want to end up simply having visited this world.

Whatever your preferred language, whether that of the psychologist, priest or poet, do you too share this deeply human longing?

As I have been forging my own unique path, I have gleaned three important lessons from Dante:

1) To Lean Into My Lostness:

Dante reminds me that whenever I find myself lost, I need to embrace it.

For there seems to be a rule, written into the DNA of this mysterious universe, that if we humans are ever to find, or forge, our own unique paths, we must be willing to get lost first. And if we are not willing to lean into that lostness, the opportunity for a deeper, more real, more adventurous life is lost.

Why?

Because it is only by letting go of the known, to such an extent that we no longer know where we are, or who we are, that we create enough empty space in ourselves to truly discover and receive a deeper, wilder, more fully alive way of being, a way that is fully infused with our own unique character, soul, heart and spirit.

In her book ‘A Field Guide To Getting Lost’ Rebecca Solnit distinguishes between ‘losing things’, which is about the familiar falling away (“objects and people disappear from your sight or knowledge or possession; you lose a bracelet, a friend, the key, but you still know where you are. Everything is familiar except that there is one item less, one missing element”) and ‘getting lost’, which is about the unfamiliar appearing (“the world has become larger than your knowledge of it”). About this ‘getting lost’, she writes:

That thing the nature of which is totally unknown to you is usually what you need to find, and finding it is a matter of getting lost. The word ‘lost’ comes from the old Norse ‘los’ meaning the disbanding of an army… I worry now that people never disband their armies, never go beyond what they know… Advertising, alarmist news, technology, incessant busyness, and the design of public and private life conspire to make it so.

Now, I don’t think getting lost is something we can, nor necessarily should, want to force. In my experience, forcing things always proves counter-productive in the end. But, like Gandalf turning up at Bilbo’s door in ‘The Hobbit’, in response to Bilbo’s old cry for adventure, I do believe life has an uncanny way of calling us out into the wild unknown at some ripe moment, often when we are least expecting it.

Whenever these moments arise, I need to remind myself that if I do find myself in a dark wood with the straight way lost, I must not turn back. I must not head home along the path I have trodden before, back to the stale safety of the known, but instead find the courage to stay in the world that has become larger than my knowledge of it, to stay lost in the woods of uncertainty, and wait for a new way to open.

2) To Be Prepared For Pain:

There is no way we can forge our own unique path in life without experiencing pain. As Dante discovered, before he could ascend to the heights of heaven he must first descend to the depths of hell. The psychologist Carl Jung articulated this same realisation perfectly, when he wrote:

It is not by looking into the light that we become luminous, but by plunging into the darkness. However, this is often unpleasant work, and therefore not very popular.

As Rebecca Solnit reminds me, for all true and deep transformation, the early stages of change or cure often mimic deterioration and decay. Cut a chrysalis open, and you will find a rotting caterpillar. She notes that the name for butterfly in Greek is “psyche”, the word for soul. However much we would wish it otherwise, it seems that our soul’s demand of us the courageous determination of the caterpillar, the courageous determination to stay with the phase of decay, the withdrawal, the era of ending that must precede all new beginnings.

In my experience, there is no way round this pain, this darkness, this decay. But, just like our lostness, I have found that if I do embrace this pain rather than fighting or running from it, in due time I do strike gold. When I do steady myself for it, trusting the process, putting my faith in the mysterious refining that goes on in the furnace of suffering, I do reap the rewards of my pain, in time.

As the holocaust survivor, and author of ‘Man’s Search for Meaning’, Victor Frankl put it:

What is to give light must endure burning.

3) To Find Good ‘Soul Friends’:

Last, but by no means least, Dante reminds me of the vital necessity of good ‘soul friends’.

In his epic, Dante is guided by Virgil, Beatrice and Saint Bernard, without whose guidance and companionship he would have no doubt perished along the way. On my own journey towards self-actualisation, towards my vocation, towards making of my life something particular and real, I have on a few occasions found myself in particularly dark places, places I may not have survived if I had not had good, wise, compassionate friends and guides to fall back on.

In their book ‘The New Monasticism’, Adam Bucko and Rory McEntee talk about this type of friendship as spiritual direction, writing:

A spiritual director is not primarily a teacher or guru per se. Rather, they are primarily a spiritual companion, a soul friend on the path of the heart. Spiritual directors help to locate mentees in the truth of their life and give them a dangerous permission to follow it with dedication. Spiritual directors also help to develop the gift of discernment and can give much-needed encouragement during dark times, encouragement that only one who has passed down a similar road before can give.

I am personally indebted to my “soul friends”, who have at times saved me, and it is because of the precious gift of their soul friendship to me, that I now firmly believe we all need wise “soul friends” in our lives. Someone who also knew this truth well was John O’Donohue, who wrote the following blessing:

May you be blessed with good friends.

May you learn to be a good friend to yourself.

May you be able to journey to that place in your soul where there is great love, warmth, feeling, and forgiveness.

May this change you.

May it transfigure that which is negative, distant, or cold in you.

May you be brought in to the real passion, kinship, and affinity of belonging.

May you treasure your friends.

May you be good to them and may you be there for them; may they bring you all the blessings, challenges, truth, and light that you need for your journey.

May you never be isolated.

May you always be in the gentle nest of belonging with your anam ċara.

As I come to the end of this Dante inspired newsletter, I wish John O’Donohue’s blessing for you. And I leave you with the challenging words of Rebecca Solnit:

Leave the door open for the unknown, the door into the dark. That’s where the most important things come from, where you yourself came from, and where you will go.

Exercise for the Month:

In his wonderful book ‘A Path With Heart’, Jack Kornfield writes:

When we ask, "Am I following a path with heart?" we discover that no one can define for us exactly what our path should be. Instead, we must allow the mystery and beauty of this question to resonate within our being. Then somewhere within us an answer will come and understanding will arise. If we are still and listen deeply, even for a moment, we will know if we are following a path with heart.

It is possible to speak with our heart directly. Most ancient cultures know this. We can actually converse with our heart as if it were a good friend. In modern life we have become so busy with our daily affairs and thoughts that we have forgotten this essential art of taking time to converse with our heart. When we ask it about our current path, we must look at the core values we have chosen to live by. Where do we put our time, our strength, our creativity, our love? We must look at our life without sentimentality, exaggeration, or idealism. Does what we are choosing reflect what we most deeply value?

For this month’s exercise, I invite you to carve out some quality time for yourself to have a conversation with your heart. Find a calm, relaxing place, make yourself comfortable, settle into your body and breath, and when your mind has stilled and you feel yourself centered and ready, begin to speak with your heart directly. Let the conversation unfold gently and organically. Be open to surprise.

Poem for the Month:

This month’s poem is ‘one small step’ and is inspired by a line of the poet Antonio Manchado:

Pathmaker, there is no path; You make the path by walking, By walking you make the Path.

You can see the poem below, along with its accompanying illustration by Mike Sprout, which makes up part of our collection ‘This Place’.